By Brian Johnson

The Theory of Constraints was developed in 1984 by Dr. Eliyahu Goldratt, an Israeli business management consultant. Goldratt’s key insight was that every process has at any time one key constraint that limits production flow. Once the constraint is identified and resolved (through a combination of quick fix and more structural improvements), the next constraint becomes apparent and can be similarly attacked. The Theory of Constraints (ToC) has since become a powerful management tool frequently used in supply chain and manufacturing. ToC can also provide insight into the policy maker actions required to hit aggressive regulatory and production targets for EV sales.

In terms of ToC, we can think about the EV value chain as having four broad areas: demand, downstream, midstream and upstream. Recent legislation contains a slew of demand, downstream and midstream carrots (incentives and subsidies) and sticks (tighter CO2 targets and state-level ZEV mandates) which are intended to spur rapid EV adoption over the next decade. From a ToC perspective, lawmakers have directed substantial subsidies toward demand and midstream battery manufacturing– but have largely not addressed the upstream constraints around mineral extraction, refining and processing. Indeed, recent moves by Treasury to open up the $7500 EV credit for leases on vehicles without regard to battery content dilutes the already weak upstream incentives. As midstream and downstream volumes grow, the cost and availability of critical battery materials (both raw and refined) could put EV production and sales goals at risk. The challenge is even greater when overlaid with the desire to shift upstream supply chains away from China.

Failure to address the upstream constraints threaten adoption of EVs across the board. Either by reducing sales volumes or by setting up a vicious cycle of higher commodity prices and supply shortages. This downward spiral then puts further price pressure on EVs which, in turn require, greater government subsidies to offset. Given the long lead times for minerals projects, policymakers in 2023 need to make substantial progress addressing critical constraints for critical minerals. Key action steps should include;

- Balance phase-in of critical mineral requirements for the Section 30D consumer tax credits to continue to send market signals to incent upstream activity while considering reforming the lease credit to incent battery mineral production in North American and allied countries;

- Move forward on permitting reforms, to reduce time frames while respecting environmental issues;

- Use the Energy Department’s ATVM loan program to support upstream projects; and

- Continue to work with allies on responsibly accelerating mineral projects.

Overview of the EV value chain from a ToC view

In terms of ToC, we can think about the EV value chain as having four broad areas (Figure 1):

- Demand: end consumer and business demand;

- Downstream: automaker vehicle assembly (supply); charging infrastructure;

- Midstream: battery cell, module and pack manufacturing; and

- Upstream: battery raw material mining, processing and battery anode/cathode manufacturing.

Simplified EV value chain

Source: Roland Berger, SAFE analysis

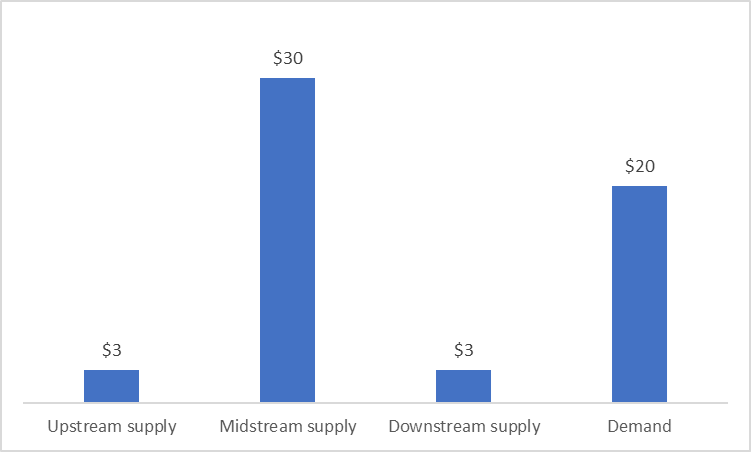

Demand side subsidized by over $20 billion

Early in the adoption of EVs, policymakers focused on downstream constraints, both on the demand side (e.g., a federal tax credit, various state credits and HOV lane incentives) and on the vehicle manufacturing side (tighter fuel economy rules and ZEV mandates forcing automakers to launch EV models)2. The recent Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) enhanced and extended downstream incentives. These included extending tax credits via Section 30D for personal vehicles (up to $7,500 depending on price, income and content) and for commercial vehicles as well as grants to expand and strengthen charging infrastructure.

Overall, we estimate these actions create a pool of $19 billion of subsidies directly tagged for EVs and $20bn of general transportation funding that could in part be used for EVs.

IRA and Infrastructure subsidies by value chain step ($bn)

Source: SAFE analysis of IRA legislation

Downstream – sticks, some carrots

In terms of downstream vehicle manufacturing, the AMVP provides a carrot of ~$3 billion for funding EV assembly plants, along with extensive state subsidies (e.g, over $2 billion for Ford from Kentucky and Tennessee for its EV and battery plants). In addition, $3,750 of the consumer $7,500 tax credit requires the vehicle be manufactured in North America or Free Trade Agreement countries (although leasing may provide a loophole for imported EVs). More importantly, by tightening Federal CAFE standards and state ZEV mandates, there are plenty of ‘sticks’ to force automakers to accelerate their shift towards EVs.

Midstream battery manufacturing – close to $30 billion of subsidies

While downstream auto plants can be converted from conventional internal combustion engine (ICE) cars to EVs, midstream battery manufacturing requires de novo facilities. Indeed, to hit the Administration’s goal that EVs reach 50% of US sales in 2030 would require ~600-700 GWh of battery manufacturing capacity – versus 55 GWh installed in 2021.

Acknowledging the need for battery manufacturing capacity domestically and with reliable partners, the IRA addressed midstream constraints by providing incentives and funding for battery cell and pack manufacturing capacity in the U.S. and FTA countries.

These include the Section 45X subsidies of

- $10/kWH for battery module manufacturing;

- $35/kWh for battery cell manufacturing (subject to rising targets of battery materials coming from NAFTA or FTA allies);

- 10% of production costs for ‘electrode active materials’ – worth ~$5/kWh.

The IRA subsidies are already having an impact on capacity planning. Prior to the IRA, close to 700 GWh of plants were planned3; since then OEMs and battery companies have announced more than $25 billion in investments,4 making it likely that by 2030 North America will have close to 1,000 GWh installed. That is enough for ~10 to 13 million battery electric vehicles5 (enough to reach the Administration’s goal of 50% of sales by 2030).

Upstream – ‘economic signals’ but not permitting relief and risk of backtracking

As midstream and downstream volumes grow, the cost and availability of critical battery materials (both raw and refined) could put the EV goals at risk. The challenge is even greater when overlaid with the desire to shift upstream supply chains away from China. For example, by 2030:

- Lithium demand for EVs outside of China is likely to be ~185,000 metric tons, while NAFTA production in 2022 was only 6,000 metric tons and US & FTA countries 87,000 metric tons;

- Nickel demand for EVs outside of China is likely to be ~1.1 million metric tons, while NAFTA production in 2022 was only 148,000 metric tons and US & FTA countries 308,000 metric tons;

- Cobalt demand for EVs outside of China is likely to be ~142,000 metric tons, while NAFTA production in 2022 was only 5,000 metric tons and US & FTA countries 13,000 metric tons.

However, lawmakers have largely not addressed the upstream constraints around mineral extraction, refining and battery component manufacturing.

The eligibility requirements for the $3750 Section 30D consumer tax credit is the principal – but awkward – mechanism to incent development of upstream critical mineral capacity. In order for auto buyers to collect the $3750 tax credit, EV producers will need to source an increasing amount of battery minerals from the US or from FTA countries (40% of content value in 2023 stepping up to 80% in 2030). The intent is to send ‘economic signals6’ to encourage development of domestic and FTA partner resources. However, the loophole that allows the $7500 credit to be applied to leased EVs – regardless of country of origin or battery content – significantly weakens the economic signals contemplated by IRA.

In addition, the DOE has allocated $3bn (from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Act) to support domestic production of key battery minerals. However, policymakers have not addressed the constraint created by the U.S. permitting process, which is particularly important as mines can take 10 years to permit and develop and processing facilities three to five years.

In summary, failure to address the upstream constraints would slow or reverse the scale curve improvement in EV affordability. If vehicle prices do not steadily fall as projected, it will threaten mass EV adoption. The vicious cycle will follow whereby additional government incentives (to offset high EV prices) then boost demand for the vehicles that cannot be supported by existing supply chains, thus causing commodity prices to spike.

To avoid this cycle and fulfill the promise of EVs for our economic and national security requires a more serious public-private effort to address constraints across the vehicle and battery supply chains.

Brian Johnson is the Founder of Metonic Advisors and focused on the mobility and auto tech space. Prior to that, Brian was a Managing Director of Barclays Investment Bank covering the automotive industry after a career in consulting as a Partner at McKinsey and Accenture.