By: Joe Quinn, Executive Director of the Center for Strategic Industrial Materials, SAFE

Used in everything from building and electrical infrastructure to the aerospace and defense sectors, aluminum is prized for its high strength-to-weight ratio and is ubiquitous in our in our modern lives. It is estimated that Americans are never more than six feet away from a piece of aluminum—which is common in consumer products but also provides essential structural support to our energy and transportation infrastructure. Military grade aluminum is also irreplaceable in defense manufacturing, making aluminum supply security a national security imperative.

Domestic aluminum demand is projected to rise from 11.5 million to 16.6 million metric tons by 2030, driven by infrastructure, energy, defense, and packaging needs.

However, we take aluminum for granted and must be more deliberate about how we use (and re-use) this strategic industrial material. While the defense and aerospace sectors require high-purity primary aluminum, many domestic industries can meet their needs with secondary aluminum.

Aluminum scrap must be prioritized as a strategic asset, and we must reconsider recycling practices and policies concerning secondary aluminum—not only to meet increasing demand, but to prevent this valuable resource from flowing to our competitors or adversaries.

Aluminum recycling: how does it benefit the U.S.?

Infinitely recyclable, aluminum can be transformed from a beverage can into a window frame and back again. Recycling aluminum only uses 5% of the energy needed to make new, or primary, aluminum. Energy costs are the largest impediment to domestic primary aluminum production, making these energy savings especially vital. Today, the secondary market has replaced primary methods as the leading producer of American aluminum, now accounting for more than 80% of total U.S. aluminum production.

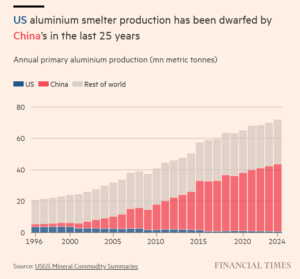

The primary sector has dwindled since 2000 from 24 smelters to just 4 – with only two operating at full capacity. The United States fell from being a global leader in aluminum production to now being dwarfed by China. The U.S. has compensated for shortfalls by becoming increasingly dependent on imported primary aluminum, a strategically dangerous decision.

An absurd practice: meeting domestic demands through imports while exporting precious scrap metal

The Trump administration rightly wants to rebuild our primary aluminum sector, but doing so will take years. In the interim, bolstering secondary aluminum production through recycling is an obvious choice. And so is ensuring adequate volumes remain in the U.S.

The U.S. is exporting increasing volumes of scrap metal, shipping over 2 million metric tons overseas in 2023 alone. Absurdly, much of this ends up in nations that reprocess and resell the aluminum back to the United States at a premium—an economically and strategically shortsighted process. As the U.S. fails to recycle aluminum and instead ships its scrap to China, we become even more dependent on adversarial supply chains, allowing them to expand and strengthen their recycling capabilities, while we undercut our domestic capability.

Exporting scrap metal at a time of need hinders us from meeting our aluminum demands without adversarial help. China has demonstrated its willingness to impose export and trade restrictions on critical raw materials, as seen with restrictions on gallium, germanium and antimony, and ongoing restrictions on rare earth magnet export restrictions. With these materials, China owns production of the raw material. And in the case of aluminum, the U.S. is currently providing the raw material to China.

The path towards aluminum supply chain security

America has the scrap supply, technology, and policy tools to lead in global aluminum scrap metal recycling and to meet much of its future demands through the secondary market. Several policy approaches could allow the U.S. to preserve and process critical aluminum scrap metal domestically, including: modernizing trade enforcement, imposing precision export restrictions, and investing in domestic capabilities and technologies.

- Narrowly scoped export restrictions on high-grade, processable aluminum scrap, especially used beverage cans (UBCs) and automotive sheet, can ensure aluminum feedstock supports U.S. manufacturers first.

- Updating the Harmonized Tariff Schedule (HTS) to reflect quality and processability empowers U.S. Customs and Border Protection to differentiate between strategic recyclable scrap and waste, preventing critical assets from being offshored.

- Providing federal support and incentivizing investments for advanced, AI-powered sorting and recovery technology and infrastructure will help maximize domestic utilization of scrap material, aligning processing capabilities with rising demand.

The U.S. government has the legal and institutional tools to act decisively. The President and Congress can use several tools to employ policy that supports America’s aluminum recycling sector, including:

- Section 232 and 301 authorities can justify targeted scrap export controls on a national security basis, ensuring our scrap is readily available for domestic manufacturers and necessary defense applications.

- FAST-41 and the Defense Production Act (DPA) can fast-track infrastructure development and incentivize public-private partnerships, building America’s recycling and manufacturing industrial base.

- The Department of Energy and Department of Commerce can integrate scrap policy into ongoing metals-for-defense initiatives, guaranteeing scrap availability complements primary and downstream investments.

- Congressionally approved appropriations for regional recycling hubs, manufacturing projects, and facilities can complement direct investments and updated trade measures and restrictions.

Taking advantage of our scrap, or ceding the future of aluminum to China

China has invested in over 15 million metric tons of aluminum recycling capacity, representing 70% of global investment in the space. At the same time, the U.S. is landfilling 800,000 metric tons of aluminum used beverage cans (UBCs), which exceeds the United States’ primary production supply capacity, rather than supporting American workers and factories through recycling. With modest investments in recycling and processing technologies, the U.S. could recover and redeploy much of this scrap into vital applications, countering China’s dominance in the secondary aluminum market.

A targeted scrap metal export ban, dedicated investments in processing technologies and capabilities, and updated trade measures represent a strategic opportunity to reclaim our position on aluminum. If we fail to take advantage of our abundance of scrap aluminum, we will waste a competitive advantage—ceding the future of aluminum to the Chinese.