By: Skip Estes, Director of Government Affairs, SAFE

The late comedian George Gobel once quipped, “If it weren’t for electricity, we’d all be watching television by candlelight.” While tongue-in-cheek, Gobel’s quote demonstrates the irony that modern America relies constantly on the electric grid for its standard of living, yet the public pays it little mind. That’s changing. Economic trends are demonstrating a shocking rise in electricity demand, which must be met with new generation and power lines.

For most of the 2010s, energy pundits bemoaned a potential “utility death spiral” due to stagnant demand growth and distributed generation sources. Fast forward to today and Washington is in a panic that we’re coming up short on supply of electrical power while lacking the infrastructure to deliver it—and the byzantine federal permitting process is increasingly the main culprit.

Fortunately, the imperative to meet power demand is well understood in Congress and the Trump Administration, and permitting reform has become a framework for a new bipartisanship.

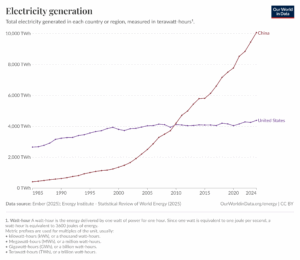

Between 2005 and 2020, there was little growth in American electricity consumption. Energy efficiency and generation technology improvements counterbalanced growth in demand, and the main investments in grid resources were retrofitting generation and upgrading existing power lines.

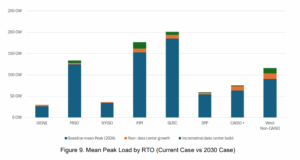

In 2022, Dominion Energy notified data centers located in Loudoun County, Virginia, that their power needs could not be met, not because of a lack of generation, but because Dominion could not move power to their location. The local transmission network relied upon to deliver large power loads was at capacity, and new lines would have to be built.

As analysts have noted (including SAFE in our “Wired for Defense” report), building new transmission lines can take upwards of 10 years. In the next five years, the Department of Energy expects power demand to increase by over 100 gigawatts, or almost 15%. That math doesn’t work.

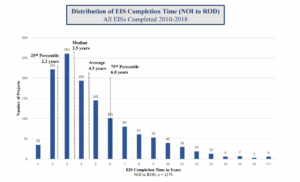

Permitting a transmission project alone can include as many as 60 separate steps across seven or more federal agencies. Resulting in over a decade of delays per project. For example, the TransWest Express project took nearly 15 years to gain federal approval. This does not even include the state, local, or tribal authorities that often have their own distinct permitting processes.

Transmission and grid infrastructure are not the only defense-critical energy projects obstructed by the current permitting regime. Critical minerals projects also face unacceptable uncertainty and massive delays. A Department of Energy study has found many federal agencies, including the Department of Defense, required almost five years on average to complete NEPA-required environmental impact statements. To confront Chinese critical mineral dominance, the U.S. must expand and open new mines to access America’s wealth of natural resources. Unfortunately, permitting a new mine can take between seven and ten years, while permitting the same mine in Australia or Canada would take a fraction of the time.

Source: Executive Office of the President Council on Environmental Quality, Environmental Impact Statement Timelines (2010-2018), 2020

Both Democrats and Republicans are increasingly in agreement that federal permitting policy is unacceptable. In 2024, former Senator Joe Manchin (D-WV) and Senator John Barrasso (R-WY) worked together on the Energy Permitting Reform Act (EPRA). If passed, EPRA would have been the first multi-sector permitting reform package since the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act of 2015. This bill would have guaranteed lease sales for oil, gas, wind, and geothermal, improved mine permitting, excluded low-impact transmission projects from the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), and placed limits on NEPA litigation.

Most recently, House Natural Resources Committee Chairman Bruce Westerman (R-AR) and Representative Jared Golden (D-ME) introduced the Standardizing Permitting and Expediting Economic Development Act (SPEED Act). This proposal would enforce NEPA review timelines, clarify the scope and original intent of NEPA, and reform environmental litigation to reduce frivolous lawsuits while maintaining a public permitting process.

This glimmer of bipartisanship in Congress has been made possible by the cross-aisle realization that current permitting policies are one of the largest barriers to maintaining American leadership in advanced computing and AI development.

There is no shortage of opinions in Washington as to the single most important issue facing the United States. Depending on the lawmaker, one may say reliance on Chinese supply chains, another may decry declining military readiness, and yet another may warn about the effects of climate change. Permitting reform is imperative in meeting the challenge of each of these issues. This explains the bipartisan interest in reforming NEPA and other environmental protection statutes. Whether the U.S. can resolve each of these issues depends entirely on the pace at which new infrastructure is built and new energy is made available to power manufacturing, electrification, and advanced computing. Perhaps the true irony is that it is the grid that has the power to finally break through the famous Washington gridlock.